Katachi

by Beth Cardier, Ryuji Takaki and Shu Matsuura

Katachi literally means form, but the concept has complex meanings that can only be found in the Japanese understanding of the term. In Japan, the science of form is nurtured from generation to generation by an energetic community of researchers, known as “the Society for Science on Form, Japan,” who study the way form and function are related. Informally, we say the “Katachi Society.”

Newcomers might ask, why should we extend our notion of form to katachi? One answer is, because it can reveal how form facilitates interactions, and it can lend new insight to fields across the arts and sciences.

The word “katachi” is a composite of “kata” (pattern) and “chi” (magical power), thus it includes meanings such as “complete form” or “form telling an attractive story.” It can reveal the relationship between shape, function and meaning; the Society studies it in relation to everything from self-inflating sails for spacecraft, to new solutions for molecular biology, and even attractive mechanisms such as pop-up books. It is likely to be an important consideration in future designs of user-friendly devices, such as advanced computer interfaces. The Society‘s understanding of form has ancient cultural roots, which could be most clearly explained through two examples, the tea ceremony and Kanji characters.

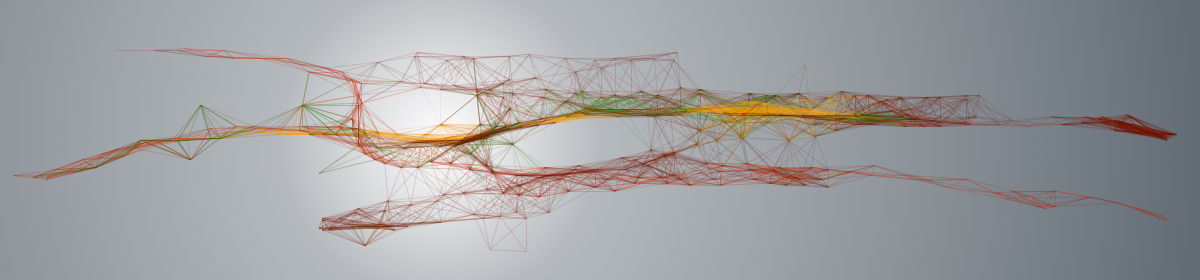

The figure below expresses the object of the Katachi society. It shows that the object is to understand Katachi from the standpoints of four fields of research. For that purpose these four fields must interact with each other. Thus, the activity of the Katachi society is expressed visually as a tetrahedron.

The Tea Ceremony

The tea ceremony was developed in Japan in the late sixteenth century, and has a simple format — a host serves tea with some sweets, the guests drink it and then express thanks; that’s all.

Foreigners are often mystified as to why such a minimalist event can require years of training. But the motivation for this art is common to every culture: imagine a talented host from any country whose manner is so easy that guests are wrapped in a mood of quiet happiness.

In the tea ceremony, this ability has been refined into a skill that combines materials, meaning, and mood. Those with high ability know how the guest’s experience can be improved with careful preparations of tools, reflective conversations, and natural yet well-controlled body motions. Physical movements embody the intended meaning of the event, so the whole environment becomes a signifier. Small innovations are often introduced into the style of hospitality to suggest the personality of the host.

Kanji

The unique Japanese understanding of the relationship between form, function and meaning can also be found in the pictographic writing system that extended across Asia 4,000 years ago. This method of communication began in ancient China, when a writing system was developed in which characters carried meanings as both idea and picture. Basic concepts such as “rain” and “dragon” were given respectively simple pictures, while more complex concepts such as “electricity” were expressed by combinations; for example, adding “rain” and “dragon” produces “lightening”, which later changed to “electricity” (for more detailed explanation, see * below). This writing system is called “Han zhe” in China and “Kanji” in Japan.

Governments in countries under strong influences of China had to adopt this pictographic writing system in order to receive political regulations or to keep diplomatic relations, but the pronunciation of the characters was not controlled. These regions were able to maintain aspects of their local culture through different aural versions of the same written words because the common meaning existed only in the shape.

This means that a certain kind of communication through forms has been practiced among different cultures for more than 1,000 years.

A Call for a New Study

The study proposed to be managed through this website welcomes interest from researchers every form-related field, and every country. The nuances of the concept can sometimes take time for non-Japanese to learn but are very useful and rewarding. Even some Japanese may be puzzled by the relevance of such principles to other applications, because practices such as the tea ceremony and kanji-reading are very familiar cultural elements. Yet they are among the many examples that can illustrate the underlying notion.

Even though the meaning of katachi must be considered deeply in order to realize it, some members of the Katachi Society also bear in mind the advice of Sen-no Rikyu, who founded the practice of the tea ceremony:

“Keep in mind that the tea ceremony is no more than making tea and drinking it.”

Something similar can be said of computer interfaces, relatively mundane things we hardly notice. But a consideration of the notions of katachi could bring about a re-evaluation of interface design. A computer interface is no more than a system with which users encounter easily and finish with happily.

It takes great effort to realize such a “natural” thing. For example, at a symposium in Japan a few years ago, the topic concerned the qualities of icons for electric machines: the icon for “power-on” is made of a circle and a short vertical line. The “power-off” is indicated by a black square. On the other hand the elements of Kanji standing for human actions have mostly asymmetric shapes, which could indicate that symbols for actions should be designed asymmetrically. The icons in use contradict this, so a consideration of kutachi could improve how we understand them.

Before we direct you to other paths of information, here is one final example of katachi. When many guests visit a house and go through a garden without guide, as is the case in the tea ceremony, the host must take care so that guests do not go in the wrong direction. In such a case the host will put a small stone wrapped with a rope on the path. This suggests to guests that they stop and turn around. The rope indicates that this stone is placed artificially. In the west, a logical solution would be to erect a fence or barrier, but guests feel more comfortable interpreting from a natural sign. After the below links to related websites, you will find such a sign.

Further information:

The homepage of Forma, the journal of the Society for the Science on Form

The journal now has an e-library page accessible here.

It features four articles:

— Flow visualization (Collection of pictures by a Japanese experimentalist), whose text part is edited by R.Takaki.

— Research of Pattern Formation (A thick report of a research project supported by a financial grant from the Japanese government (chief: R. Takaki, editor of report: R. Takaki)

— Science on Form – Two Proceedings of the International Symposia in Japan organized by the Katachi Society (in 1985 and again in 1988).

The Society frequently focuses on topics of interest and releases a special issue of Forma on the subject. Below are some popular special issues:

“Crystal Souls” by Haeckel translated by A. Mackay (Vol.14, No.1-2, 1999)

“Proceedings of 2nd Katachi U Symmetry Symposium,” Tsukuba, 1999, Part 1. (Vol.14, No.4, 1999)

“Proceedings of 2nd Katachi U Symmetry Symposium,” Tsukuba, 1999, Part 2. (Vol.15, No.1,2, 2000)

“Selected papers from 2nd Katachi U Symmetry Symposium,” Tsukuba, 1999. (Vol.16, No.3, 2001)

“Special Issue for Structural Color” (Vol.17, No.2, 2002)

“Special Issue for Neuro-science” (Vol.19, No.1, 2004)

“Special Issue for Golden Mean,” edited by J. Kappraff (Vol.19, No.4, 2004)

“Special Issue for The Beauty of Formative Art” (Vol.21, No.1, 2006)

![]()

![]()

![]()

* According to a well known dictionary that was written by Shizuka Shirakawa, who was a researcher of Chinese shell bone character, the kanji of electricity (in the modern sense), 電, is a connection of “rain” and “lightening”, and meant thunder lightening. The lower part of “electricity” was a pictorial expression of lightening which waves right and left. The kanji of dragon, 竜, had originally a different shape from lightening. Dragon had a snake-like realistic expression at its origin. The lightening, 申, had on the other hand a meaning of presence of god’ power. People later unified the two concepts “dragon” and “lightening” and began to express with the same shape.