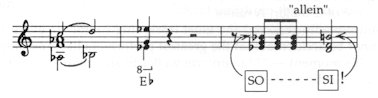

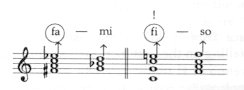

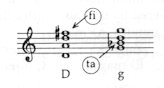

Fig. 9

Mozart puts his finger on the main feature

of the mentioned ’fermentation’, realizing that the birth of SI entails

the possibility of the augmented triad: the Sprecher sings an augmented

triad melody,

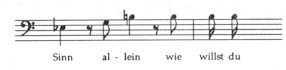

Fig. 10

and this possibility is exploited by Mozart

at other points as well: think of "Zurück!"

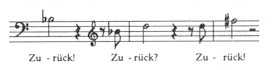

Fig. 11

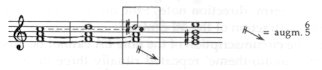

Reference must be made to an essential

connection between chords with a common third, of which the classical

study of harmony forgets to mention the most important fact: namely, that

(in the overwhelming majority of cases) chords with a common third appear

as the VI. degree — as the VI. degree of the major and minor scale.

The VI. degree of C major is A minor and the VI. degree of C minor

is Ab major.

The common third (the note C) is identical with the key note. It is not

the most effective way of pitting a major against a minor to put C major

opposite C minor, but to have their VI. degrees contrasted: A minor

and Ab major, just as in

the following Brangäne-Tristan dialogue. When Tristan (and with him

the Ab major) appears, he

almost ’loses his mind, his consciousness’ (though in an ironical sense

here): Wagner presents a genuine ’minor effect’ to us:

Fig. 12

As for the Sprecher’s scene, the minor

VI. degree and the major VI. degree determine the formal outline of the

entire dialogue: the Sprecher enters the stage on the minor VI.

degree (with an Ab major

harmony) and when he exits, Tamino arrives at the major VI. degree

(A minor key). This is what carries the liberating thought:

VI.

degree of C minor: Ab major

are chords with a common third.

VI. degree

of C major: A minor

Mozart undoubtedly reserved the most intriguing

harmonic event to the development. It cannot be accidental that the greatest

performers like Toscanini and Bruno Walter placed this moment — "Man opferte

vielleicht sie schon?" — into the focus of the plot dramaturgically as

well.

Already the polar turning-point

indicates that Mozart is to ’try out’ his most daring harmonic effect on

us: D minor and B major are separated by six accidentals, just like the

keys a tritone apart (e.g. F major and B major).

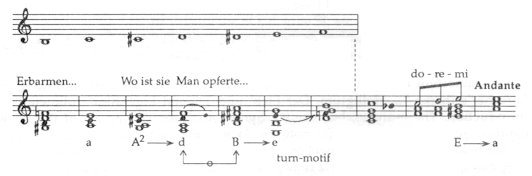

Fig. 13

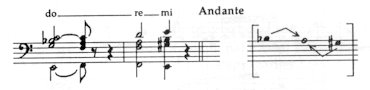

But let us go back to an earlier point.

(Formerly, I devoted a detailed study to this problem.) In a major tonality

the tonal centre is DO. That causes the predominance of the TI-DO

leading-note steps. In minor keys, however, it is not necessarily LA

that constitutes the tonal centre, but much rather the note MI: the core

of a melody mostly comprises FA-MI steps (think of the main idea

in Mozart’s great

G minor Symphony, or the main theme in Beethoven’s

Appassionata

sonata:

Db-C turns in bs. 1-24).

In our tonal system, the symmetry-pair of the TI-DO leading note

step is the FA-MI step; Mi is the mirror image of DO.

4)

The note MI (note E in A minor) can most

effectively be approached from two sides: from the directions of

FA and RI (F and D#). What is the ’augmented six-five‘ chord?

It is a special chord typical of the minor tonality obtained when the V.

(MI) degree is prepared not simply by the IV. degree,

Fig. 14

but the MI centre is approached from both

sides with chromatic steps: with FA-MI and at the same time RI-MI ’direction

notes’, (that is, with F-E + D#-E turns). In such a case this

tight harmonic relation will almost produce a ’physiological’ effect, as

it were!

Fig. 15

Between each statement of the three-times

repeated motto-theme ("Sobald dich führt..."), which in terms

of form expresses the attainment of the goal, the augmented six-five chord

occurs, lending special weight to the MI centre. The chord first

accents the word "Licht", then underscores the sentence "saget mir: lebt

denn Pamina noch?"

Fig. 16

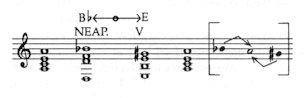

The nucleus of this harmony — F major

— is the VI. degree of the tonic A minor. B major preparing the development

is, on the other hand, the counterpole — the tritone — of F major. The

model of the polar turn must be traced back to the Neapolitan

chord. The Neapolitan chord and the V-I step following it serve to circumscribe

a tonal centre note, with semi-tone steps, to boot; in A minor key,

the notes Bb and G#

chromatically head towards the note A: 5)

Fig. 17

By the way, we know from earlier experience

that the Bb major Neapolitan

chord is nothing else but the substitute chord of the subdominant

D minor.

The above quoted polar turn ("Man opferte...

sie schon?") is based on a similar attraction — proved unquestionably by

the renderings of Toscanini, Bruno Walter or Karajan — : the melody falls

over the central

E note.

Fig. 18

This time, too, FA and RI play the role

of the ’leading notes’ from two sides (I prefer to use the term ’direction

notes’: the meaning of both FA and RI is expressed by the sphere of attraction

of the

MI centre).

However, the circumscription of the note

LA

cannot be missing, either. Before the outburst of the ’motto-theme’ repeated

ritually three times ("Die Zunge bindet Eid und Pflicht... schwinden")

the notes Bb and G#

perform a similar task: 6)

Fig. 19

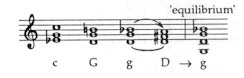

In terms of taxonomy, the ’symmetry-pair’

of the G major dominant seventh is the B-D-F-A subminor chord. The character

of the latter is far more lyrical and melodious (’singing’): thanks to

the

LA note. Instinctively, that is how it became the backbone of

the repeated motto-theme:

Fig. 20

The dialogue has a recurring ’leitmotif’

which owes its existence to the direction-notes — precisely to an

element that is the opposite of the leading note step. Let us do ’violence’

upon the leading note of the V. degree (e.g. the note B of G major) by

modifying the note B to Bb

(instead of the tonic resolution): that is, let us have the major third

(B) replaced by a minor third (Bb).

This charges the note Bb

with tension, turning it into a dissonant element, a ’direction note’ requiring

further leading — towards D major. From that point onwards the function

of the dominant is not performed by the G major but by D major (= the secondary

dominant: the dominant of the dominant). The task of the tonic belonging

to D major (i.e. G minor) is simply to restore the equilibrium —

as it was expressed by a great conductor in connection with "Ja, ja, Sarastro

herrschet hier".

Fig. 21

Following the onerous admonition "Tod

und Rache dich entzünden" (concealing an augmented six-five again),

Tamino surfaces with the G major dominant:

Fig. 22

The old priest suddenly tones down his

voice: instead of G major we hear G minor and the continuation conforms

to what was described above.

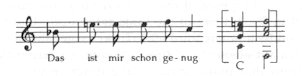

The G minor and D major chords shown in

Fig.

21 constitute a symmetry-pair, mirroring each other taxonomically.

In this sense, the mirror image of the note Bb

(TA) is F# (FI). It would be redundant to mention this, had

Mozart not made use of its opposite upon the return of the motif. This

time the emphasis is laid not on TA but on FI, which immediately gives

the motif a ’challenging’, provocative character: it becomes a threat to

murder, striking the key of passionate protest, of indignation. The key

is F major (or F minor): "das ist mir schon genug". Were this to occur

in a classical oratorio, the homophonic melody would be answered in the

following way:

Fig. 23

What accounts for the sharp ’challenge’

is the replacement of the C major domi-nant by C minor (the passionate

minor dominant), and just like earlier, the natural continuation is in

G major — where the note B means FI, striking the tone of danger

and threat.

Fig. 24*)

The scale-degrees FA and FI

have a distinguished place even among the ’direction-notes’. FA pulls downwards

(to MI), while FI pushes upwards (to SO). This is a very modern idea in

dramaturgy. The introductory part of the dialogue is tied to C major,

its middle part to C minor and its related keys, while the closing

section returns to the keys without accidentals: first to A minor and finally

to C major.

The question arises what scenic moment

elicits the reprise. In Tamino, the image of the "unglückliches Weib"

(disconsolate mother) evokes the tragic G minor. For the old priest, however,

the "Weib" means something quite different. At first one might think he

is only envious (that is why the sarcastic intonation) but it shows through

the music more and more apparently that she is the opponent, or

even the ’enemy’. Isn’t it peculiar that "Ein Weib" as well as the image

of the enemy is associated with the C major chord? Let us take a closer

look at what is happening here. In G minor the Eb–D

steps give the impression of emotional FA-MI steps; the guiding thread

of the harmonies is made exclusively of Eb–D

steps (earlier I pointed out that FA–MI is the ’emotional’, introverted

element in music):

Fig. 25

As against that, when the Sprecher begins

to speak, — what a turn! — FA is replaced (ousted, to be precise) by FI,

which ushers the dialogue towards SO:

Fig. 26 (Play before it the

former example!)

In connection with the mentioned G minor,

Bb7and Eb

major turns let me refer to another idiomatic turn also behaving like a

leitmotif. In my analyses of Verdi and Wagner I termed this element the

turn-motif.

In Mozart’s music the role assigned to it is to give emphasis (emotionally

charged emphasis) to a word. When, for instance, the root of the A minor

chord is raised a semitone higher, that is, modified to Bb

(NB: the modification giving accent to the chord), a major seventh

(C7) is gained which automatically leads into the substitute

key (F major).

Fig. 27

That’s how we arrive from the first "Zurück!"

to the second gate, from G minor to Eb

major:

Fig. 28

Later we move from the G minor of "Sarastro

herrschet hier" to Eb major

in the same way: raising the basic note of G minor gives edge to Tamino’s

violent "nicht".

Fig. 29

The sentence "Er ist ein Unmensch" is

stressed by a similar motif (G minor, Bb7,

Eb

major).

Fig. 30

The same takes place after "Erklär’

dies Räthsel" (E minor, G7, C major; the raising of the

root note falling on the sentence "täusch mich nicht!"). 7)

Before sketching the tonal structure of

the scene, let us remember an analogy: Tristan’s ’dream chords’ (Brangäne’s

first monologue in Act 2: "Einsam wachend..."). Each group of chords springs

from C# major — and the nadir is reached when C#

major is followed by A minor and E minor triads:

Fig. 31

In the opera C# major signifies

the ’mother’s lap’ (the womb), the ’dream’, the ’night’ — the Nirvana.

The A minor and E minor nadir presupposes the renunciation of this, too:

after C# major A minor establishes an annihilating relation

(not to speak of the fact that the leading note within the C#

major chord [E#] is resolved unnaturally downwards),

while E minor represents a polarly distant relationship with C#

major.

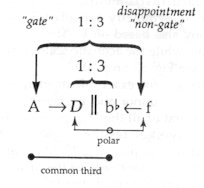

If in the cited dialogue of the Magic

Flute D major symbolizes the ’gate’ of Sarastro’s temple, the concept

of the ’non-gate’ — the moment when Tamino gets ready to leave disappointed

and ’renounces’ the gates — will be represented by Bb

minor and F minor, according to the above logic. D major

and Bb minor are complementary

keys: renouncing each other, while F minor is removed to the other pole

from D major: in our tonal system (e.g. the circle of fifths) the largest

possible distance is expressed by a difference of 6 accidentals. As if

it were the model for the Wagnerian technique: the very point where Mozart

noted in the score "er will gehen" (and the Sprecher asks Tamino: "Willst

du schon wieder geh’n?"), we find ourselves in the Bb

minor key, followed four bars later by F minor.

The contrast becomes even sharper when

it is considered that D major is prepared by a salient, conspicuously emphatic

A major dominant (almost 9 bars in length); attraction and repulsion are

made even more apparent:

Fig. 32

A similar contrast was noted earlier:

Tamino’s youthful, spontaneous utterances were expressed in B minor and

E minor, while the old priest opened up the tonal scope of Ab

major and Eb major:

Fig. 33

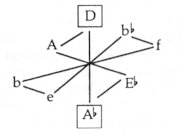

As a result of the above-described connections,

a dual, intertwining ’spiral system’ is created in which each element is

balanced off by its counterpole (its tritone-pair):

Fig. 34

Another two arguments are elicited by

the transformation in the wake of "Zurück!". In C major tonality,

the symmetry centre of our tonal system is marked by the D or the Ab

pole. The gate is evoked by D major, the Sprecher appears on the counterpole:

in Ab major. For Bartók,

the inversion of the major pentatony — DO pentatony — became

incarnated in MI pentatony, (projecting the DO pentatonic scale built on

the note D downwards of D, a MI pentatonic scale is produced). The

basic idea of Cantata Profana cannot be separated from the fact

that our tonal system (notation, the stringing of the keyboard instruments,

and in many respects the string instruments) is based on the ’d’ symmetry

axis. Bartók contrasts the DO pentatony based on D with MI

pentatony also based on D. The starting scale of the work rests on the

D=MI pentatonic frame, while the acoustic scale closing the work unfolds

from the D=DO pentatonic scale: (see Fig. 85

on p. 49) 8)

Thus the above two scales are the exact

mirror images of each other. The D=MI pentatonic scale incorporates

the G minor and Bb major

triads. The D=DO pentatonic skeleton of the finale contains first of all

the D major triad, but also the B minor triad. In The

Magic Flute, D major symbolizes the ’gate’ (cf. also Tamino’s rapture

in B minor upon sighting Sarastro’s temple). The D=MI pentatonic scale,

on the other hand, contains the Bb

major and G minor triads: at the turning point, as a consequence

of the word "Zurück!", these very ’reversed’ triads get legitimation:

first Bb major, followed

by G minor (the former after "Zurück", the latter after "Glück").

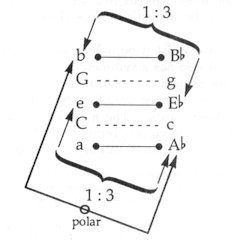

One more thing should be touched on in

connection with the outcry "Zurück!". This is what triggers off the

radical change that occurs through the entry from the ’major’ world into

the ’minor’ world. On the one hand, C major and its V. degree (G major)

ensure the tonal aura that can be schematized in the following way (every

second step in the figure rhyme in perfect fifths). The formula

also implies the possibility of B minor and E minor (as was mentioned earlier,

Tamino’s temper is governed by the positive substitute chords of

G major and C major: B minor and E minor).

Fig. 35

To produce the above net of fifths

(Fig. 35a), a single C major (or A minor) triad would suffice. Should we

replace C major by C minor, the fifth steps would take the shape

above (Fig. 35b—the relative key of C minor is Eb

major, etc.).

Looking at the two schemata side by side,

one realizes that the relationship between the alternating major and minor

third is

reversed. The second row of thirds goes along the same

path as is covered by the music after the shock of "Zurück!":

| Zurück! |

Glück. |

Zurück! |

...hier. |

Adagio. |

| Bb major |

G minor |

Eb major |

C minor |

Ab major. |

Fig. 36

In the scheme above C major and C minor,

G major and G minor indicate a ’major-minor’ (modal) contrast. A more complicated

case of the major-minor relationship is the contrast of the chords with

a common third: Ab major

and A minor almost present an allegoric contrast (appearance and dissappearance

of the old priest). A similar contrast is created between E minor and Eb

major, B minor and Bb major.

By the same token, the chord with the common third as the enthusiastic

B minor emanating from Tamino’s personality is to become the Bb

major, which expresses the stout resistance of the gate, the shock ("Zurück!").

Tamino’s flaring up in E minor will also have a chord with a common

third: Eb major,

which projects to us the state of mind of the old priest together with

the spiritual world behind him. And if you add to that, that E minor and

Ab major, as well as B minor

and Eb major are spheres

that negate one another (complementary keys), while B minor and Ab

major are polar spheres, then the computer may help you orientate yourself

in this multidimensional network of relations.

The broad cadences illuminate the D

major episode like spotlights: Tamino is standing in front of the temple

gate. The ’map’ of the scene gives similar salience to the importance and

frequence of the G minor episodes: "Ja, ja, Sarastro herrschet hier":

a G minor arrival, right in the foreground of an explosion. And later:

"So gieb mir deine Gründe an!": G minor, before another explosion.

And yet another G minor: "das Gram und Jammer niederdrückt."

In C major, the simplest subdominant and

dominant are represented by D minor and G major. In taxonomic terms: the

symmetry-mirror

of D minor is G major. The symmetry remains intact even if we replace D

minor and G major by D major and G minor, respectively. In

this case, the notes FA and TI are replaced by FI and

TA:

in our system of notation, the nearest (first) sharp and the nearest

flat appears:

Fig. 37

(The frequency of D major and G minor

not only illustrates how the mentioned principle became one of the most

obvious instruments of ’expanding’ the diatonic system, but also suggests

how the ’acoustic’ scale: — DO-scale with FI and TA — was born in Bartók’s

style.)9)

Speaking of the 19th century, let it be

mentioned that the dominant of the A minor key: the E major chord

also has a symmetry pair, the F minor. In the C major key the symmetry

axis of the system is constituted — besides D — by the G# =

Ab note (in the notation,

it is marked by the ’middle’, the third sharp or flat, resp.). One points

upwards, the other downwards.10)

The nadir of disillusionment is scored by Mozart in the F minor

key ("... nie eu’ren Tempel sehn!"), while the development (motto-theme)

is born out of E major. F minor and E major not only satisfy the

requirements of the ’mirror relationship’, but are also chords with

a common third.11)

The Mozartian chromaticism is omnipresent

— ensuring the organic, unbroken connection between the chords. After the

statement "Die Absicht ist nur allzu Klar!" the note B leads to C, then

(extended into a major third) gets emphasis from the C# note

so that the latter could proceed to D as the leading note. The role of

the neckbreaking polar change (D minor—B major) seems to imply that D should

turn into D# and resolve in E. Via the ’turn-motif’, however,

this E also rises to F, which eventually becomes reconciled in the central

E note.

Fig. 38

The basic motif of relief, of ’smoothing

out’ is the DO-RE-MI motif (also on the stage of Wagner and Verdi).

Significantly, the three-times repeated motto-theme is prepared by this

phrase (see Fig. 19 on p. 143).

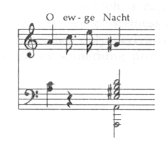

The cathartic moment follows the introduction

of the motto-theme: "O ew’ge Nacht" — Mozart has the tonic (bass) and the

dominant sound at the same time —hence the time-paralyzing, static

effect:

Fig. 39

The true unfolding — the absolution —

is brought along by the flute solo of Andante. The dual — Eb

major and C major — stage of The Magic Flute has often been discussed

by analysts (Eb major as

the tonality of being initiated, being an ’insider’ in the sacred secret);

this dual tonal stage prevails in the examined dialogue as well.

Compared to C major, the Eb

major chord assumes its expressive character from the notes MA and TA (Eb

and Bb). When the flute solo

taming the beasts is intoned and Tamino’s aria "Wie stark ist nicht dein

Zauberton" is begun, the stage lighting also changes: in our tonal system,

the mirror image of TA and MA are the notes FI and DI – the

aria is dotted with FI and DI colours, which produce the ’fabulous’ natural

aura of the scene:

Fig. 40

In connection with the ’sanctified’ key

of Eb major, let me remind

you of the Sprecher’s theme "... Heiligtum. Der Lieb’ und Tugend Eigentum"

following his introduction. The more so, because it ‘rhymes’ with the closing

act of the above Quintet, quoting almost ’note for note’ its Bb

major melody "Drei Knäbchen jung, schön, hold und weise, umschweben..."

and its smoothingly blissful parallel thirds. Deepening the chords

in thirds (a typical feature of the ’motto’-theme as well) is well known

from the classical literature: it promotes the constant expansion of the

’inner stage’, it keeps intensifying the radiance of the theme.