Fig. 101

At its every step, the score of Music for Strings,

Percussion and Celesta betrays that the composer’s inner hearing was

stereo. What is more, Bartók was acquainted with principles which

the pioneers of modern stereo recordings did not begin to develop until

the early sixties.

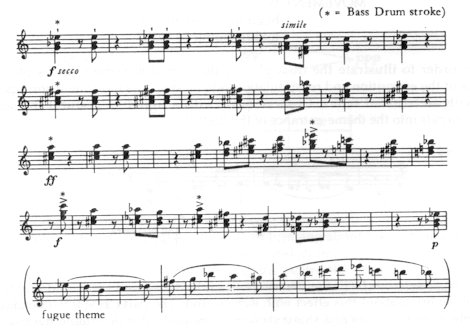

In the principal theme of the second movement, the left

group of strings is taken over by that on the right (see Fig.

99 on p. 59), while in the principal theme of the fourth movement,

the right orchestra is answered by the left, in accordance with the fact

that – as opposed to the energetic short-tempered impulses of the beginning

of Movement II – the mood of the finale is relieved and joyous. We have

already experienced the crucial importance of the fact that the two orchestras

are united at the recapitulation of the second movement (likewise

the sound becomes ’centralized’ in bs. 74 and 114 of the finale).

Melodies appealing to ’emotions’ – as the secondary themes

of Movement III – come forward consistently from the left, whereas

thoughts of ’spiritual’ content come from the right. It is not even

conceivable otherwise: at the end of Movement IV, where the fugue-theme

returns in ’diatonic’ form, the tune is heard from the right-hand stage

– the spiritual quality of the thought is in this way significantly extended.

Further it can be observed that the ’impressionistic’

character goes hand in hand with the spatial polarization of the

tonality; and conversely, the more ’expressionistic’ the character of the

music, the more the external space loses its importance and the tonality

becomes homogeneous – mono-sounding. This in itself conceals exceptional

possibilities! E.g., at the climax of Movement I – when all our attention

is focused on the inner dynamics and tension – Bartók suddenly

transforms the polarized sound into ’mono’ sound, that is, he makes the

two orchestras play the same parts. The reverse is just as effective;

but as opposite laws apply to the ’chromatic’ and ’diatonic’ techniques,

in the diatonic world this also comes to pass the other way round: the

homogeneous sound becomes a ’stereo’ sound at the climax – in much the

same way as when we have ascended a hilltop, the landscape all at once

opens up before us. The opposition of the left and right often produces

the sensation of ’here’ and ’away’ (the music of the next movement offers

an interesting example of this).

Ferenc Liszt also writes about this symbolism in

a poetic letter (Florence, 1839) on Raphael’s painting Saint Cecilia.

’The painter places Paul and John on the left of the picture: the

former is deeply absorbed in himself, the outer world ceases to

exist for him; behind his giant figure immense profoundities are lurking.

John is a man of "attractions" and "feelings"; an almost feminine face

looks out at us. On the other hand, Augustine on the right of Cecilia,

maintains a cool silence ... he abstains even from the most sacred emotions

– constantly fights against his feelings. On the right edge of the picture

stands Magdalene in the full splendour of her worldly finery; her whole

bearing suggests worldliness, her personality radiates a sensuousness

somewhat evocative of Hellas... Her love stems from the senses and adheres

to visible beauty. The magic of sound captivates her ear faster

than her heart is possessed by any supernatural excitement.’

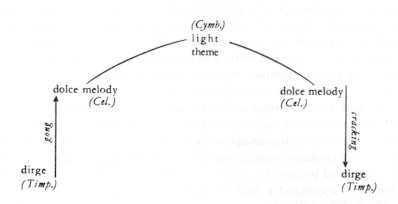

Movement III is a magic nature music. Its form

again rests on symmetry – on a five-part ’bridge form’ (the order of the

themes being A-B-C-B-A): on the one hand, the dirge melody of the first

and last sections, and on the other, the alluring siren music of the second

and fourth sections rhyme with each other; the sharp flashes of the third

theme mark the centre of the bridge. To put it another way, the form of

the movement delineates a spacious cupola, rising from the sobbing dirge-melody

(A) up to the ethereal siren-song of the secondary theme (B); then an undulation

– stirring up the whole orchestra – prepares the midpoint: the ’light’

effects of the climax (C), (see: Fig. 56 on p.

36) in order to lead back to the starting point, in reverse order of the

themes (melody B and finally, A).

Erich Doflein believes the xylophone rhythm at the beginning

of the movement to have been inspired by the wooden drum of Japanese No

dramas. That Bartók resorts to such sound-effects not for their

own sake is proved by these very pages of the score. From theme 1, the

sobbing lament song, the ’fume’ of a gong-stroke rises to the ethereal

clear dolce-melody of the celesta-violin (theme 2); in the recapitulation,

however, since the order of themes is reversed, the previous dolce-melody

is suddenly stopped by the ’snapping’ of the strings (produced by slapping

the strings against the fingerboard), and leads back to the dirge. And

whereas the dirge-melody and its nocturnal F# tonality is deepened

by the shuddering sound of the timpani (i.e. the lowest drum effect),

a high-pitched cymbal effect indicates the centre of the movement

– and the key of light: C.

Fig. 102

As in the previous movements, the peak of the cupola (the

counterpole of the movement) also transmutes the action in its content

– and this is movingly expressed by the recapitulation of the secondary

theme:

Fig. 103

The most essential effect often escapes the attention

of performers: this theme reappears in canon, and from the ’imitating’

part of the canon (cello) Bartók requires a more intensive

dynamism than from the ’leading’ violin: the cello is piano, the violin

pianissimo. Thus the effect arises: the melody becomes a recollection,

a memory image: with the help of the canon, it shifts in space and time

(attention and mind are divided into two) – it takes place on a divided

double-stage and, owing to the stressed imitating part, a stronger light

is thrown on the more distant stage. We point this out because in Bartók’s

recapitulations, canon melodies of slow space usually play the role of

’memory’, remembrance, reminiscence.

Here the reminiscence effect is enhanced by something

else. The violin is heard from the left, and the imitating cello from the

right side of the stage. As on modern stereo stage, the left is associated

with ideas of ’inside and here’ – while the right with ideas of ’outside

and far’.

The’memory’ character makes us realize why the tune must

end with the break of the strings (a strong pizzicato so that the string

rebounds off the fingerboard). As a consequence of the crack, the basses

groan and the dirge-melody returns.

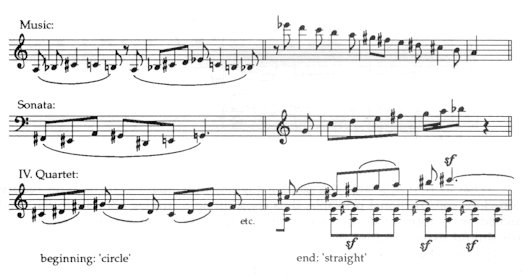

The finale contains the poetic solution of the work. The

solution lies in the fact that the leitmotif of the work, the ’closed’

fugue-theme – which hitherto occurred in a narrow a chromatic form – reappears

towards the end of this movement in a wide diatonic form: in the ’open’

sphere of the natural overtone scale (see Fig. 107

on p. 65).

The transformation from closeness to openness is already

revealed by the principal theme: the ’circular’ melodic lines of the first

movement are here extended to ’straight’ scale-lines:

Fig. 104

Bartók’s closed chromaticism can be represented

by the symbol of the ’circle’, while his open diatony can be seen in the

symbol of the ’straight line’. The themes also become assimilated to these

emblems: the chromatic system is most naturally combined with the circular,

whereas diatony with the straight melodic line (scale-line). The opening

and closing themes of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion,

Music

for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, and of the Fourth String Quartett

are shown here:

Fig. 105

In Dante’s Divine Comedy, the symbol of the Inferno

is also the circle, the ring, whereas his Paradise is symbolized by the

straight line, the arrow, the ray. The concentric circles of the Inferno

narrow till they reach the Cocytus – the circles of Paradise, however,

expand into the infinite Emphyreum. In the Comedy we frequently

come across the transformation of the circle into straight line, and vice

versa. The poet approaches, for instance, the denizens of the Purgatorio

in this way: ’You, who are bent by life, keep circling to straighten

out again’ (Purg. XXIII); or later on, looking into the light-river: ’Into

roundness it seemed to change its length’ (Purg. XXX).

How characteristic of Bartók’s simplicity that

when the diatonic fugue-theme returns, he is satisfied with a unisono

melody (on the G string) – the artistic solution is achieved virtually

without the assistance of technical means. Even when repeated, the melody

is coupled only with simple major-triads, through which the sound becomes

solid and solemn, like an organ – signifying that the fugue-theme which

was born out of the resounding chaos of the first movement, through the

piercing humour of the second movement, and the spell of nature in the

third, has finally arrived at its poetic fulfilment.

But what does this ’openness’ actually mean? The hypnotic

effect of the first movement is the result of the fact that — during the

progress along the fifth-circle — at every moment, in every phase of the

circumvolution, we are necessarily aware of the positions the theme occupies

in relation to the centre. Bachofen’s mythological analyses call our attention

to how deeply and indelibly the ritual act of ’going round’ has its roots

in human nature (the excitement of ancient circus-games or of modern horse-races,

Dante’s journey through the rings of hell or the lovers of the Magic

Flute going round the circles of the ’fire and water ordeal’ would

produce quite a different impression on us should we disrupt this outer

framework of the action).

In the closing movement all this happens differently.

Here each new episode opens up before us with the result that the material

of the former section ’bursts open’:

Fig. 106

What at first appears as a sort of ’montage’ or ’mosaic’

form, is in reality a conscious constructional principle, thus constituting

a striking contrast to the single-arched ’wave-form’ of the first movement.

— If our earlier observations were correct, we should expect to find the

decisive turn again after the central theme: in the unexpected ’change

of scene’ of b. 114 (a change in key, too, because instead of the expected

C major, it switches over to the F# counterpole!). (See: Fig.

176 on p. 93).

The diatonic entrance of the fugue-theme marks the most

beautiful ’opening’ of this kind. This is already reflected in the scale

of the melody: its notes are derived from the natural overtone sequence

(C-D-E-F#-G-A-Bb-C)

– that is, the theme is introduced not as a melody but rather the projection

of a harmony:

Fig. 107

This is the source of the pervasive clarity, the hymnic

floating of the theme and, as mentioned earlier, its open spatial effect.

Over the theme — again from the right — a piping major-sixth organ point

particularly underlines this effect (the major sixth in Bartók’s

tonal world may justly be called the ’pastoral sixth’). This theme is the

key to the comprehension of the work. Is it not conspicuous how vividly

this tune — this unisono melody — is pervaded by the metrical pulsation

of ancient hymns, suggesting a text, the Hellenistic sense of form: infinite

in its asymmetry, but at the same time, clear in cadence and lilt – like

the conscious revival of the famous Seikilos hymn,

Fig. 108

of that Seikilos ode which is simultaneously both a drinking-song

and an epitaph, wisdom and love of life – a balance between life and death.

NEXT

CONTENTS