|

COLOUR IS STRUCTURE

LIZ COATS

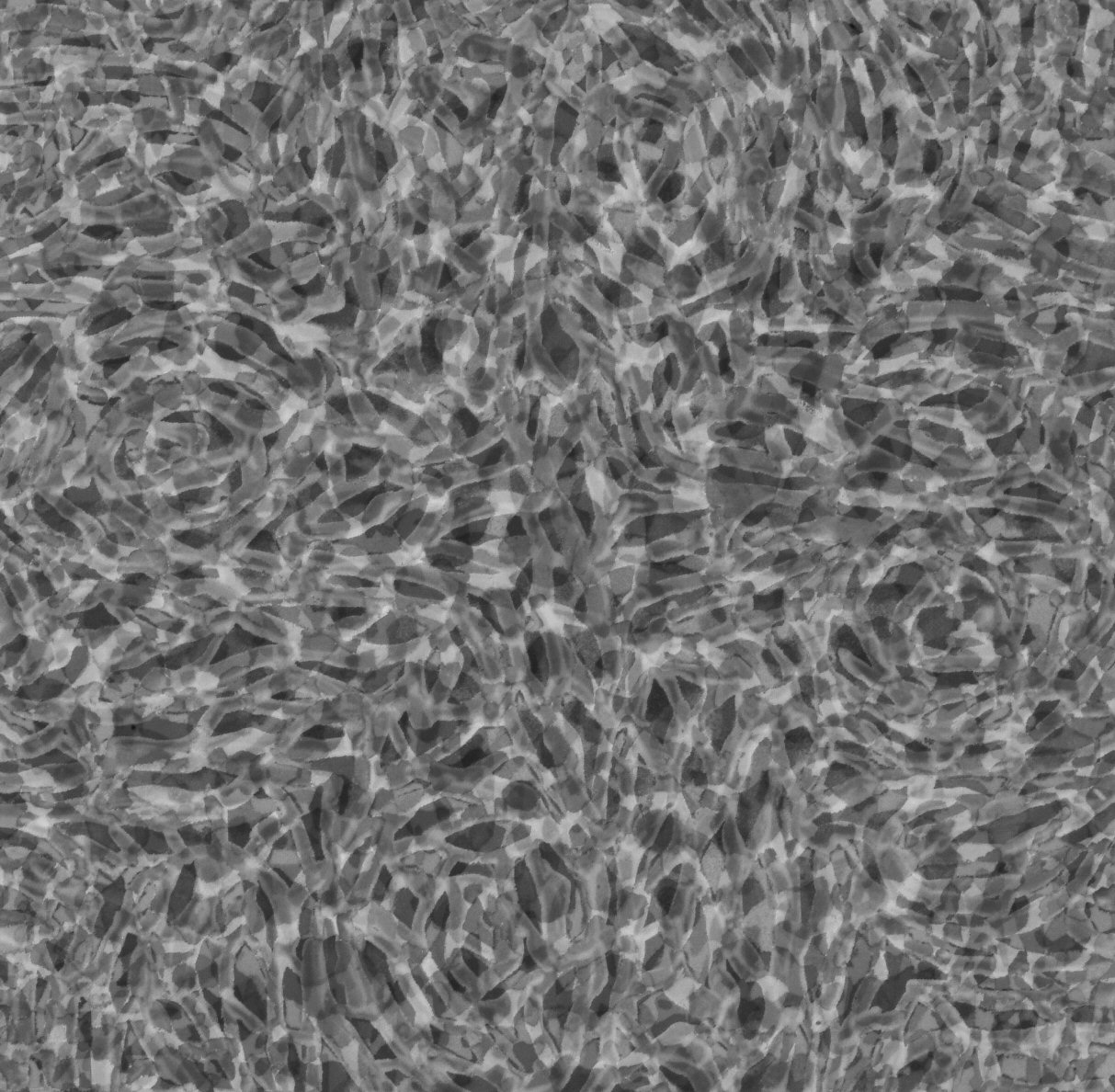

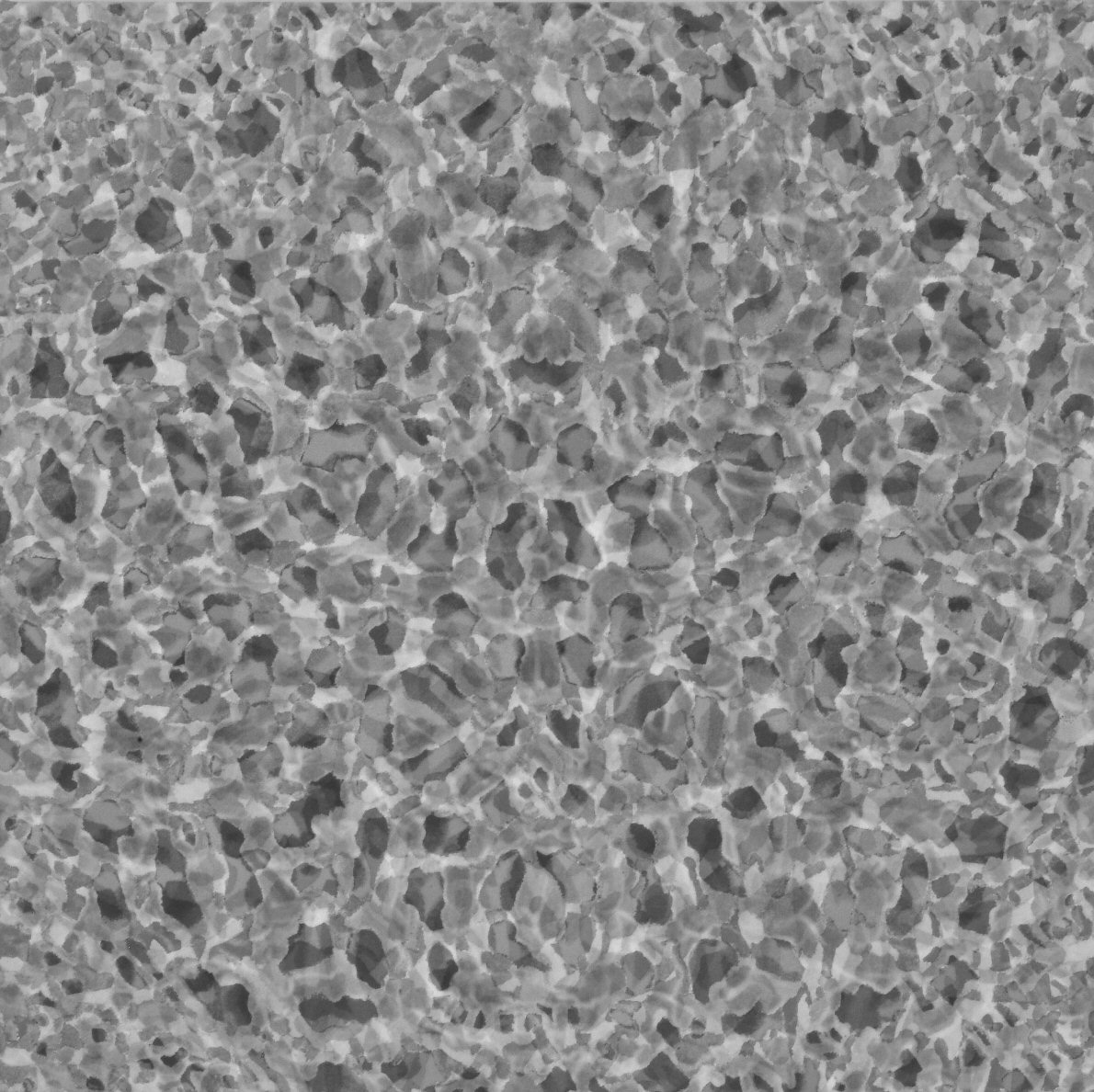

"There are some days when it seems to me that the universe is nothing but a continuous stream, a river of aerial reflections around the ideas of man." (Biederman, 1958, p. 13, translation from Gasquet 1921, p. 122) In his record of meetings with Cézanne, Joachim Gasquet recounts that Cézanne imagined the picture plane as a flowing process surface where the colours penetrate each other, extending into a single, unified field. But Cézanne also realised that to submit to this fugitive or fleeting aspect of nature meant being subsumed by the totality of nature’s complexity that would forever elude vision. So it was necessary to devise an organising structure appropriate to the physical painting plane that included visual access to an experience of ‘deep’ space. This was Cézanne’s life project and one which challenged his concentration and application to the limit. More than 100 years ago, understanding that the eye is educated by contact with nature, Cézanne devised a simplified conceptual framework of geometry for seeing nature’s complex forms. His friend, Emile Bernard records that Cézanne came to realize that the visual field becomes concentric. Wherever the body moves in space, in constantly changing circumstances, light communicates in layers of images from all points and in every direction in which we turn. At any position, the eyes establish a plane of symmetry always parallel to the plane of the layers of images coming from the point focused on. Images emanate from every point within a vast globe, of which our eyes are the symmetric centre. Images are the conjunction of light and the function of vision in a state of corresponding symmetry. Being guided by nature, small planes of pure colour are Cézanne’s solution. The geometric framework however, must not remain visible because it is colour in light that shapes and combines forms in visible nature while structural organization is reflected in the placement of the colours themselves. A concentric order defines all possible positions that spatial planes can take in three-dimensional space. If we see the plane nearest to our eyes as the pivotal plane, then the construction of a series of colour patches across the whole painting surface will be relative to this ‘centre’. Brushmarks are applied across the whole picture plane, not towards individual, ‘sculptured’ shapes defined by areas of painted light and shade within a perspectival scene. Relationships between overlapping planes of colour describe their place in deep space and will suggest a visual order and rhythm that circulates within the containment of the picture plane. Over a lifetime of working to depict his sensations of nature that were true to the reality he saw, and translating this experience to the formal symmetry of a picture plane, Cézanne established a new direction for painting process that combined structural stability with an awareness of temporal processes. The image became more than an expression of the limited self of the artist. Cézanne’s translation radically questioned painted depictions of the world of solid forms and through his analysis of methodology, opened up many possible interpretations for painting. My own painting practice has been informed by the development of colour-structural approaches to painting that separated from direct adherence to nature and representation of solid objects. Painters are always aware of the dualisms between what is known and observed and the processes through which a painting is constructed. For me, organization of colours becomes the inherent structure and the subject for painting. For the 2001 Congress in Sydney, I wrote: "For a non-figurative painter, recognizing the space around us as deep and seemingly chaotic and engaging with symmetry as a connective bridge within the fluid and volatile colours of a painting, dispersed and divided concepts can be brought into energetic contact without a single viewpoint or defining edge. This is all about thinking and making structurally in order to see into phenomena. Perhaps one might consider painting as a feedback loop in which the time-base is hidden. An image field is contained and assembled through progressive decisions. Evolving patterns within the colour layering process provide a stream of options, rebalancing interpretation and lessening the hold of logical determination. There could be a simple periodic system within each image; additional colours suggest further variations, while anticipation is lessened and the work becomes complete unto itself.’ I’ve talked in various ways about making paintings in previous conferences, with word constructs that I am aware will meet with other disciplines. But now all I really want to do is describe in a direct and simple manner what is going on in the making. I search for simple language forms that describe the gap between intention and the manual processes. Those simple, consecutive decisions that build into complexity. I think of experiences of meeting in the everyday world, where unexpected coincidences appear to turn and face one squarely. Out of that recognition, some understanding of a beautiful continuity beyond one’s self is apparent. Those intangible moments of recognition in daily life enter into the activity of painting, bringing the desired animation to those surfaces. Without narrative imagery, I work for a convergence of colour and structure that holds light and also conveys an exchange of experience. Searching for a logic in life as it is lived and learning not to take anything for granted, I have felt strong inner guidance built through long practice and observation. I don’t entirely agree with where I came from, so determined free will has been the fuel by which I have moved out of those places and conditions that were familiar, when that familiarity served to slow down my sensitivity to surroundings and alertness to the beauty inherent in constant change. As a young woman I had an idea that making visual images was a way through feelings of hurt and pain and criticism, to neutralize violence and mediate understanding. I wanted to make paintings that might communicate something of the liveliness and beauty that I knew existed beyond my own turmoil. Eventually, instinct and experience guided me to a slow and progressive approach to painting, seeking results that were understood through observation in practice. Painting for me has become a major source of my understanding of the world. I came to symmetric formats almost instinctively, as a holding pattern to balance fluctuations and volatility in colour sequences. I was interested in irregularities of detail in those colour formations as much as overall balance and harmony. In the process nothing is concealed, while outcomes are not entirely predictable. I rely on the guiding structures established at the beginning of the process. Those sometimes wild oscillations with firmness at the functional core; the corrective balances that nature contains and the colours revealed in light, while not reproducible, are qualities for comparison. Combinations of pre-planning

and ‘in the moment’ activity have become accentuated as I have moved from

inner city warehouse/studio living to a rather wild coastal town with extreme

weather fluctuations. Within this now familiar environment, I am made acutely

aware of the temperatures of the day, growth patterns in vegetation and

time passing with the seasons. Observance of the natural world in all its

complexity and unpredictability holds my attention now and influences choices

within paintings that are otherwise entirely conceptually conceived.

References Biederman, Charles (1958) The New Cézanne, Winona, Minnesota: The Leicht Press. (Biederman includes quotations from:

Gasquet, Joachim, (1921), Cézanne, Bernheim-Jeune, Paris).

|