|

Paulus Gerdes Mozambican Ethnomathematics

Research Centre, C.P. 915,

Abstract Well known in many variations — from Egypt to Mexico, from Norway to China, from Turkey to the USA, from Morocco to New Zealand, from Indonesia to Ghana, from Senegal to Brazil — is a decorative motif in the form of an octagonal star or an octagonal flower. The octagonal design motif appears woven on textiles, knotted on carpets, laid-in on wood, knitted on pullovers, sewn on quilts, cut out in leather, embroidered on cushions, etc. It appears also on twill-plaited mats and baskets. In this paper, I will present the examples of octagonal designs I encountered so far on twill-plaited mats and baskets. I will propose the hypothesis that one of the possible cultural-historical roots of the decorative motif in the form of an octagonal star — that is one of the possible roots of the imagination the motif embodies — may lie in twill plaited toothed square designs. The paper will be concluded with the presentation of other types of octagonal designs and structures in basketry and a second hypothesis. Dedication The paper is dedicated to the late Stieg Mellin-Olsen (1939-1995). He encouraged the study of what he called folk mathematics (cf. Mellin-Olsen, 1986). At the end of the seminar ‘Mathematics and Culture’ he organized in September 1985 in Bergen (Norway), he gave me a knife with a leather cover in which an octagonal star was cut out (Figure 1). In Norway the design is called the ‘eight leaves rose’ and appears also on baskets, dresses, woven or embroidered on tablecloth (see Photograph 1), and in traditional knitting. It is found also on decorations on bone and wood dating back to the age of the Vikings (information from Nora Linden, Stieg’s wife). Stieg asked me where could lie a possible origin of this idea of the octagonal star. I promised him to reflect about the question. The time has come to try to fulfill the promise.

Photograph 1: Norwegian table cloth In the books Ethnogeometrie

(Gerdes, 1991a), Sobre o Despertar do Pensamento

Geométrico (Gerdes, 1991b) and The Awakening

of Geometrical Thought in Early Culture (2002),

I analyse the origin of several other geometrical concepts in cultural

activities.

Design cut out in leather (Norway)

Figure 2

Some octagonal stars and flowers on objects in the author’s collection Figure 3

Examples of octagonal designs Figure 3 presents some octagonal designs on objects in the author’s collection (Brazil, Egypt, India, and Turkey). Figure 4 presents some further design motifs from West India. Figure 5 displays some ‘Kairouan’ and Bedouin knotted carpets motifs design from Tunisia. Figure 6 presents some examples of octagonal designs motifs on Mexican Indian textiles.

Design motifs from Rajasthan (West

India)

Carpet designs motifs from Tunisia

Design motifs on Mexican Indian

textiles

Although the designs from Tunisia and Mexico in Figures 5 and 6 are from carpets and textiles, they may be realised by plaiting mats. The same is true for the octagonal flower designs on textiles from Thailand in Figure 7 and on the coil Yakima basket from the USA in Figure 8. Could it be that they had their origin in the twill plaiting of mats and that the forms were transposed to other materials? And once transposed, could they be liberated from the restrictions imposed by the original context of plaiting in two orthogonal directions, and assume new forms invented by creative artisan-artists?

Octagonal flower designs on textiles

from Thailand

Design on a Yakima gathering basket

collected in 1940 in Toppenish, Washington

The second Thai octagonal flower has a diameter of 17 strands Figure 9

Catalogue Photograph 2 shows a twill-plaited

box in the author’s collection. It comes from China. On its cover appears

a toothed square with an octagonal star. Its diameter measures 33 strands.

As measure of the diameter we may take the number of vertical (or horizontal)

strands needed to plait one copy of the octagonal star design (see the

example in Figure 9). Photograph 3 shows

a mat from the Tabaru (Halmahera, Indonesia).

Photograph 2: Chinese basket (author’s collection)

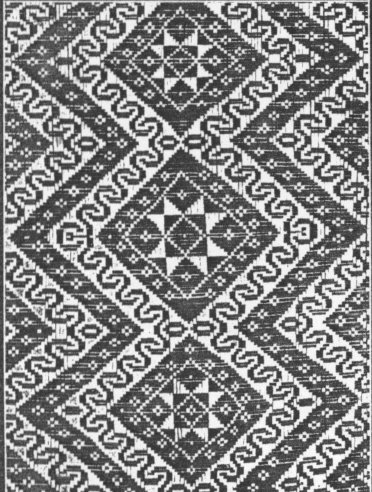

Photograph 3: Mat from Halmahera, Indonesia [reproduced from Bezemer 1931, p. 23] Table 1 presents a list of the toothed squares with octagonal stars I so far found on twill-plaited mats and baskets. These toothed squares come from China, Fiji, Indonesia, New Zealand, Thailand, Tonga, and North America. They are illustrated in Figure 10.

Design from Sulawesi

Design from Flores

Design on a Cherokee basket

Design from the Tebida-Dayak

Plaiting design from Sulawesi

called ‘permata saogoe’

Plaiting design from Sumatra called

‘kembang manggis’

Design on a Maori mat

Design on a Maori mat

Design on a basket from Suva (Fiji)

Design on a mat from Halmahera

Design from Sumatra

Design on a mat from Bali

Design on a Cherokee rivercane

market basket, ca. 1950

Design on a Chitimacha basket

Design on the bottom of a market

basket from Tongatapu

Design on a mat from Halmahera

Design on a Cherokee basket

Design on a Chinese basket

Design on a mat from Halmahera

Design on a mat from Halmahera

Design on a mat from Halmahera

Design on a mat from Halmahera

Design on a mat from Halmahera

Design on a fan from Thailand

Design on a basket from Madagascar

Catalogue of twill-plaited octagonal stars Figure 10

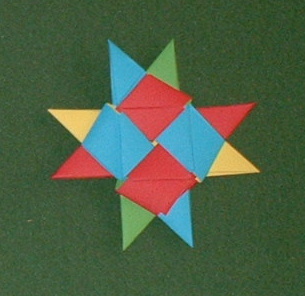

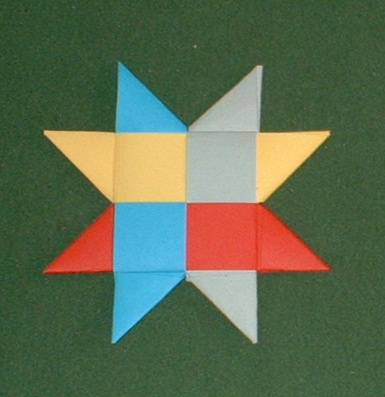

First Hypothesis Let me now try to sketch a hypothesis of how these and other octagonal star and flower motifs might have been inventively imagined in the context of twill plaiting. Consider a nested toothed square composed of, for example, 9 smaller equal sized toothed squares (schematically represented in Figure 11a). Reflecting about such a nested toothed square, an artisan may imagine a toothed square with equally sized toothed squares at its corners (see Figure 11b). Now raises the question of how to "fill up" the rest of the initial toothed square. The artisan-geometer may start with the weaving of triangles on the sides of the larger toothed square (see the schema in Figure 11c). The next step in the creative process might be ‘making visible’ in one way or another the diagonals and midlines of the larger toothed square (Figure 12a) or by extending the right angle sides of the triangles (Figure 12b), leading to the imagination of the octagonal designs in Figure 13.

Schematic representation of the first phase in the genesis of octagonal star designs

Schematic representation of the second phase in the genesis of octagonal star designs

Octagonal design structures Figure 13 The process described

is a reconstructive sketch of a possible cultural-historical genesis of

some octagonal forms that then may be interpreted as stars or flowers or

whatever. And looking to the examples of twill plaiting and historically

younger decorative contexts as textiles, carpet knotting, wood work, that

are presented in this paper, artisans from diverse parts of the Earth were

engaged in comparable activities of imagination, application and interpretation.

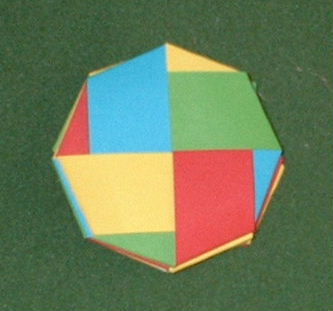

Other cultural contexts This hypothesis should not be considered absolute and the only possible. Other cultural contexts may have stimulated the emergence of the visualisation and conceptualisation of octagonal design motifs. These other cultural contexts might even be other instances of basket weaving. Photograph 4 shows two coiled baskets from Swaziland. Photograph 5 shows an octagonal star interlaced in the way as has traditionally been done on Malaita in the Solomon Islands (see Pendergrast, 1987, p. 44). Maria Dedò, professor of mathematics at the University of Milan (Italy), showed me how she had learned as a child to interlace another octagonal star (see Photograph 6). Photograph 7 presents an interlaced octagonal buttom on a Copi basket from the South of Mozambique.

Photograph 4: Coiled basket from Swaziland (author’s collection) Photograph 5: Interlaced octagonal star (Solomon Islands) Photograph 6: Interlaced octagonal star (Italy) a: Octagonal knot on a Copi basket (author’s collection)

b: Octagonal knot made out of coloured card board strips Photograph 7 Also other types of twill-plaited octagonal designs are possible. As a first example, Figure 14 displays the centre of a circular plate I bought in the 1982 at a market in Nairobi (Kenya).

Centre of a circular plaited tray (Kenya) Figure 14 Second hypothesis Figure 15 displays a traditional octagonal-circular design on Chitimacha baskets (Louissiana, USA). If we look the the distribution of the small unit squares, i.e. the places where the horizontal strands jump over only one vertical strip, the regular octagonal structure is very visible (Figure 16). To go from one unit square to the next, one moves like a horse on a chess board. Chitimacha design

Distribution of unit squares Figure 16 Figure 17 shows an octagonal design on a mat from Aceh (North Sumatra, Indonesia). A ‘chess-horse-distribution’ of unit squares is also visible on several designs from Borneo (see Figure 18).

Design from Aceh (North Sumatra, Indonesia)

Design from Borneo

Figure 18 Photograph 8 displays part of a basket from Borneo, where in each woven triangle (Figure 19) a unit square, a toothed square (Figure 20) and an octagonal design (Figure 18a) appear together. This particular situation suggests a second hypothesis: the emergence of octagonal designs from squares via toothed squares.

Photograph 8:

Plaited triangle on basket from Borneo Toothed square Figure 20

References Arbeit, Wendy (1990), Baskets in Polynesia, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu Barnard, Nicholas (1994), Artisans de l’Inde, Flammarion, Paris Bezemer, Tammo Jacob (1931), Indonesian Arts and Crafts, [Colonial Institute, Amsterdam, n.d.] Ten Hagen, The Hague [Les arts et métiers indonésiens, Ten Hagen, The Hague, 1931] Bossert, Helmuth (1990), Folk Art of Asia, Africa, Australia and the Americas, Ernst Wasmuth Verlag, Tuebingen Conway, Susan (1992), Thai Textiles, British Museum Press, London Duggan, Betty & Riggs, Brett (1991), Studies in Cherokee Basketry, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville E., F. W. van (1894), Matten van de Kabahan Dajaks, Residentie Borneo’s Westkust, Bulletin van het Koloniaal Museum te Haarlem, May 1894, 28-31 Eiseman, Fred B. (1999), Ulat-ulatan: Traditional Basketry in Bali, White Lotus, Bangkok Gerdes, Paulus (1991a), Ethnogeometrie, Franzbecker Verlag, Hildesheim Gerdes, Paulus (1991b), Sobre o Despertar do Pensamento Geométrico, Universidade Federal de Paraná, Curitiba Gerdes, Paulus (1999), Geometry from Africa: Mathematical and Educational Explorations, The Mathematical Association of America, Washington Gerdes, Paulus (2000), Le cercle et le carré: Créativité géométrique, artistique, et symbolique de vannières et vanniers d’Afrique, d’Amérique, d’Asie et d’Océanie, L’Harmattan, Paris Gerdes, Paulus (2002), The Awakening of Geometrical Thought in Early Culture, MEP Press, Minneapolis MN Gettys, Marshall (Ed.) (1984), Basketry of Southeastern Indians, Museum of the Red River, Idabel, Oklahoma Hasselt, Arend L. van (1881), Ethnographische atlas van Midden-Sumatra met verklarenden tekst, Brill, Leiden Hill, Sarah H. (1997), Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and their Basketry, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill Hoover, Herbert T. (1975), The Chitimacha People, Indian Tribal Series, Phoenix Horwitz, Elinor L. (1974), Mountain People, Mountain Crafts, Lippincott, Philadelphia Jasper, J. E. & Pirngadie, Mas (1912), De inlandsche kunstnijverheid in Nederlandsch Indië, Het vlechtwerk, Mouton, The Hague Jewell, Rebecca (1994), African Designs, British Museum, London LaPlantz, Shereen (1993), Twill basketry: A handbook of designs, techniques, and styles, Lark Books, Asheville Lehri, Roxana (1999), Folk Designs from India, Pepin Press, Amsterdam Mason, Otis T. ([1904] 1988), American Indian Basketry, Dover, New York Mather, Christine (1990), Native America: Art, Traditions, and Celebrations, Clarkson Potter, New York Mellin-Olsen, Stieg (1986), Introduction, in: Hoines, Marit Johnson & Mellin-Olsen, Stieg (Eds.), Mathematics and Culture, A Seminar Report, Caspar Forlag, Radal, pp. 1-3 Mookerjee, Ajit (1996), 5000 Designs and Motifs from India, Dover, New York, [1958] Nieuwenhuis, Anton W. (1913), Die Veranlagung der Malaiischen Völker des Ost-Indischen Archipels erläutert an ihren industriellen Erzeugnissen, Brill, Leiden Pendergrast, Mick (1984), Raranga Whakairo: Maori Plaiting Patterns, Reed, Auckland Pendergrast, Mick (1987), Fun with Flax, Reed, Auckland Revault, Jacques (1973), Designs and Patterns from North-African Carpets and Textiles, Dover, New York Rooyen, Pepin van (Ed.) (1998), Indonesian Ornamental Design, The Pepin Press, Amsterdam Samama, Yvonne (2000), Le tissage dans le Haut Atlas marocain, Miroir de la terre et de la vie, UNESCO, Paris Sentance, Bryan (2001), Art of the Basket: Traditional Basketry from Around the World, Thames and Hudson, London Taylor, Colin F. (1995), Native American Arts and Crafts, Smithmark, New York Tillema, Hendrik (1989), A Journey among the Peoples of Central Borneo in Word and Picture, Oxford University Press, Oxford Weitlaner-Johnson, Irmgard (1993), Mexican Indian Folk Designs, Dover, New York Wyckoff, Lydia L. (Ed.) (2001), Woven Worlds, Basketry from the Clark Field Collection, The Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa

|